|

When the Royal Air Force conscripts me to help defend the British Empire from the threat of German nazism in the darker days of the war, I report with other recruits to Padgate, an RAF camp near Warrington, where I part company with civilian niceties. Kitted out with an ill-fitting uniform and essential bits of equipment I am bundled off to the east coast seaside resort of Redcar to undergo basic training in military etiquette.

At Redcar, Harry Turner 2nd from left in middle row

There, we are billeted in rows of empty terraced houses commandeered between High Street and the Promenade. Nineteen of us are crammed into a neglected residence in Henry Street, with just room for beds and our kit, and left to cope with an erratic water supply, broken washbasin, light switches dangling dangerously from walls, and a shortage of light bulbs.

Hectoring corporals and sergeants attempt our rapid transformation from weedy civilians to models of military efficiency through the rigours of exercise, drill, and naked threats of personal violence. We are marched and wheeled in untidy formation on the promenade, initiated into the intricacies of arms drill, sent off on gruelling route marches in full gear, providing a diversion for the few bored but resolute holidaymakers who struggle in from Teeside despite wartime travel restrictions.

It is a hot dry summer and as a relief from the sweaty parades we are given the freedom of the deserted beaches for physical training sessions and high-spirited games, all indulged under the envious eyes of watching civilians. They are restrained from joining us by the vicious coils of a barbed-wire barrier piled up to deter attempts

at seaborne invasion.

The fact that our squad is based in Henry Street seems of little moment until the day I venture round the corner and discover myself in Turner Street. Suddenly it becomes an amazing coincidence that I should be moved right across the British Isles to finish up on a spot where adjacent streets echo my name: Henry Turner. At a time when we are having all individuality battered out of us, it strikes me as an event that just has to hint at some deep hidden significance. For days after, I bore my mates regularly during desultory conversations at breaks in the NAAFI canteen, worrying about this profound coincidence, but few are impressed.

Of course, in that far-off time I am unaware of synchronicity, a term introduced by the Swiss psychologist C.G. Jung to describe a "meaningful coincidence", which he prefers to think of as an "acausal connection" rather than the result of cause and effect. We tend to seek a cause for every effect, but Jung maintains that this ingrained belief in causality only creates intellectual difficulties, because it makes it seem unthinkable that causeless events can happen.

Out of the blue, you may think of an acquaintance you've not heard from for ages, and then the phone rings, and guess who it turns out to be... Or you learn a new word—like "synchronicity" perhaps— and suddenly it begins to catch your eye in every paper, magazine and book you happen to pick up. Apparently life is full of such surprising coincidences.

Some scientists now tell us that while cause and effect tie together many events in our world, there are also events which happen for no apparent reason at all. According to quantum theory, reality as we know it is the result of mutual interaction between the objective world and subjective observers. While cause and effect set up certain resonances and patterns in time, synchronicity arranges those resonances in step with one another, a complex pattern of events that characterises life as, somewhat bewildered, we live through it.

Thus, in 1973, during an exhibition devoted to illusion in art and nature at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London, I did some work for a competition seeking new examples of optical illusions. Months later, when I raided the accumulated sketches for ideas for paintings, I found I had overlooked the potential of an accidentally misdrawn geometrical figure.

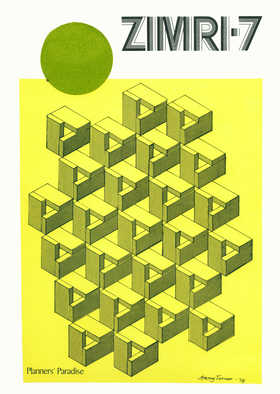

From it, I was able to devise an isometric structure that looked convincingly three-dimensional on paper though, logically, it defied realisation as a solid object. I developed this paradoxical figure in a series of drawings, one of which was snapped up by fanzine editor Lisa Conesa as a cover design for Zimri. She also prevailed upon me to write an article explaining my chance discovery. And that seemed the end of that. From it, I was able to devise an isometric structure that looked convincingly three-dimensional on paper though, logically, it defied realisation as a solid object. I developed this paradoxical figure in a series of drawings, one of which was snapped up by fanzine editor Lisa Conesa as a cover design for Zimri. She also prevailed upon me to write an article explaining my chance discovery. And that seemed the end of that.

A year later, a letter arrived from Howard Lyons, a Canadian fan with whom I'd long been out of touch, and I enclosed a copy of the magazine article with my reply. It was not until early 1976 that Howard, an amateur magician in his spare time, wrote to say that he'd passed a copy of the article to a fellow member of the Magic Circle, Martin Gardner.

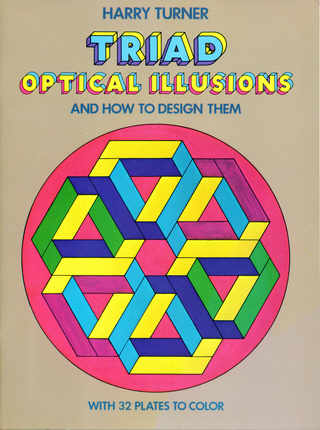

Gardner, then editing the Scientific American, expressed an interest in seeing more examples of my 'impossible objects', and I was happy to oblige since the idea had developed into an infallible method of generating infinite patterns. A mention in his column and the reproduction of some drawing must have caught the eye of the president of Dover Books in New York, who wrote asking if I'd be interested in producing a book of 'impossible object' drawings. In next to no time, all my proposals had been accepted and I was busy working on the project. Gardner, then editing the Scientific American, expressed an interest in seeing more examples of my 'impossible objects', and I was happy to oblige since the idea had developed into an infallible method of generating infinite patterns. A mention in his column and the reproduction of some drawing must have caught the eye of the president of Dover Books in New York, who wrote asking if I'd be interested in producing a book of 'impossible object' drawings. In next to no time, all my proposals had been accepted and I was busy working on the project.

I guess the concept of cause and effect is deeply ingrained in my thinking since, on publication of the book, I found myself expressing my appreciation to the editor, my Canadian friend, Martin Gardner and the Dover president as a dedication, as prime movers in the fact that my ideas saw print. But I also recognise that, lurking in the chain of events related here, there are just too many happy coincidences to be ignored. ■

|

Sounds of Music in the Midlands

|

|

"After my initial training period, I was sent on a six-month radio course at Birmingham College of Technology and early in 1943, half-a-dozen of us were despatched to Yatesbury for training on radar gear. We were in civvy billets, and the group tended to split up into classes. The RAF HQ was an office in the centre of Brum, housing the C.O. and a small staff, so official parades were few & far between.

"It was all very relaxed for wartime. There were no forms available for weekend passes – we each wrote out a copy of the official form to be signed by the C.O., and the idea was that they were collected in after each trip. In practice, I think everyone kept the handwritten passes when they left Brum – if you were on a 'crafty' and had to cross the bridge linking platforms at New Street station, they were handy to wave at curious SP patrols.

"Looking over the group in the end-of-course class photo, I could remember most of the faces, even if several names have now eluded me, but I couldn't place the bloke who towers over Tubby on the left of the pic [3rd from left]. Alas, this is the most badly faded part of the photo, but I do seem to detect a certain resemblance to the photo in the obituary for Air Commodore Frank Padfield (d. 2004/01/15).

Can it be that he was on that Brum course with me before arriving at Yatesbury? Wow! Long live synchronicity...

Fresh from my square-bashing initiation the RAF despatches me to Birmingham College of Technology for a basic radio course. It's a welcome breather to return to big city life after exile in the back of beyond; even wartime Brum has its attractions, and I can't believe my luck at exchanging the rigours of our last derelict quarters for the fleshpots of civvy billets in downtown Edgbaston. I promptly contact a local fan I know, Arthur Busby, currently serving in the National Fire Service, and still at home.

One damp chilly evening later Arthur guides me through the blackout for a fan-meet with Tom Hughes. Tom lives alone in a solid Victorian suburban residence. He's a mite older than me, an enthusiastic collector of science fiction since the late twenties, and proves to have a more practical bent than most of us young dreamers. Ushered in out of the raw autumnal atmosphere, thawing out with mugs of hot cocoa, we find he's been converting a monumental-sized mahogany display cabinet, picked up cheap, into a magnificent bookcase, occupying most of one wall.

I think of the clutter of books piled in cartons around the room back home and feel quite envious. We chat as we help him rehouse his library, an extensive collection of fantasy and sf, well-thumbed text books, and cherished files of American pulp mags: vintage copies of Amazing, Wonder and Astounding Stories, treasure trove for any devotee of the genre.

I am inclined to linger, drooling, over this feast. Then Arthur lets slip about my musical interests. Tom grins and beckons us into an adjoining room. It is filled with his record collection: hundreds of 78s, in cardboard sleeves, neatly stacked and filed in metal racks for easy access. The top of the nearby sideboard is occupied by the chassis of a five-valve amplifier and assorted transformers, linked to a gramophone turntable perched perilously on a chair seat, and to a solid-looking box housing the loudspeaker, sited in front of the chimneypiece. A toolbox crammed with soldering-iron, pliers and assorted tools, coils of wire and a miscellany of spare electrical components, conveniently props up copies of technical periodicals on the floor.

It seems that Tom is an enthusiast who spurns the low standards and compromises of mass-produced wind-up portable gramophones or the glossy veneered boomy radiograms of the day, and aspires to using the latest technology to coax the highest quality sound from his carefully-groomed shellac records. He is one of a rare breed (rarer even than sf fans) and proudly gives us a run-down on the merits of his home-built state-of-the-art reproducing equipment. He switches on: the valves flush and glow with life.

In the pause while the system warms up he asks "What d'you fancy?", waving a hand at the confusingly large choice of records spread before us. We peer at the labels. Tom's taste in music seems catholic, the emphasis on orchestral works; we leave it to him. He starts off with some ballet music by Tchaikovsky, and the room fills with enchanting sounds. He needs no further prompting but has another record out of its envelope as fast as the first finishes.

Perhaps my only criticism is that the volume control seems to range from loud to louder; the place fairly vibrates under the impact of a climax from the full orchestra. Fortunately, the dead weight of all that shellac stored on the racks, while no doubt straining the floor joists, effectively damps any unwanted resonances generated while the system is operational. Conversation ceases completely when the music is in full blast—you just listen. Momentarily I wonder how Tom gets on with his neighbours. He cheerily assures me that they are stone deaf.

In between records we debate briefly the finer points of the art: whether to use metal needles that wear out the record groove with repeated playings, or fibre thorns that preserve the record but clutter up the groove as they disintegrate in use; what angle the needle should preserve as the playing head is lowered on to the disc; the relative merits of different classes of amplifiers. Arthur remains aloof from the discussion; I guess he's heard it all before.

For our final record of the evening, I put in a request for Liszt's Dante Sonata, a piece which evokes fond memories of visits to view the Sadlers Wells Ballet with Marion. He turns the volume right up and motions us back into the library, leaving the connecting door ajar so, he explains, we can hear the music "in better perspective". We agree that it certainly adds to the ambience...

I walk back to my billet late that night, mind awash with music, a ready convert to Tom's aspirations of high fidelity sound. At the college next day, I astound the tutor with a galvanised interest in the course, hound him relentlessly for practical details of achieving good sound reproduction, file it all away for the day when the war is over and I can, hopefully, begin to catch up with the good things of life. ■

FOOTNOTES TO FANDOM #3...

one of a series of occasional pieces published by the Septuagenarian Fans Association, May 1998

© Harry Turner, 1998. |