|

|

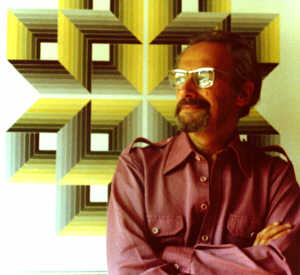

Harry Turner (1920-2009)

Artist, Science Fiction Fan & Collector

|

UPDATES

History/tribute 12 May 24

Imposs. Obj. p 3 19 May 23

Footnotes 18 May 23 |

Harry Turner's father had an unusual career—Barton Turner was an escapologist and illusionist, and a contemporary of Harry Houdini. As The Great Deville, he toured the music halls between more conventional jobs. Both were called Henry but neither ever used the name on his birth certificate. And the family name could well have been Edwards, the surname on Barton's birth certificate. But his mother remarried as a widow with three young sons, and the family became known as Turners.

Harry was an outstanding pupil at school and he had a talent for writing as well as painting. He developed a lifelong interest in space travel and science fiction, interests shared by his future wife, Marion, during the era of American 'pulps' like Astounding and Wonder Stories.

Harry was a particular admirer of the work of the artists Frank R. Paul in Wonder Stories and Elliott Dold in Astounding Stories, and also a fan of science fiction authors like H. G. Wells and Jules Verne. His favourite film was Things To Come, Alexander Korda's 1936 version of the Wells story, which he was able to view on DVD one last time shortly before his final Christmas.

As a teenager, Harry was a member of the Manchester Interplanetary Society and the co-editor then sole editor of its journal, The Astronaut. The MIS has the honour to be the only amateur society ever to launch rockets from English soil—until its exploits attracted the unwelcome attention of the local police and provide the Manchester Evening News, the News of the World, the Sunday Chronicle and other newspapers with a shock-horror story.

It was through the Junior Astronomical Association that Harry made the acquaintance (by letter) of Marion Eadie, the niece of the Glasgow artist and book illustrator Robert Eadie, R.S.W.. She was a founder member and president of the J.A.A., and they met for the first time at the 1938 Empire Exhibition in Glasgow. They were both interested in outer space; the one in how to get there and the other in what is to be found 'out there'. Harry contributed articles to the J.A.A. journal Urania in the company of rocketry enthusiasts Arthur C. Clarke and fellow M.I.S. member Eric Burgess. He added Urania to the list of amateur SF fanzines which were receiving artwork from him, e.g. Novae Terrae and Futurian War Digest, and he was also being paid for his efforts by professional magazines such as Tales of Wonder.

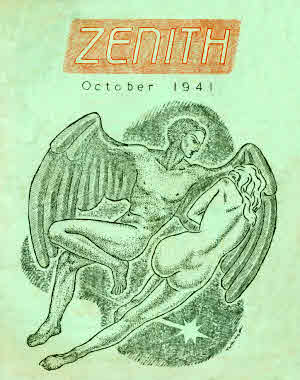

With wife-to-be Marion's help, Harry began to publish Zenith, his own SF fan magazine, in the early years of World War II. When he registered for military service in at the end of 1940, he was surprised to find that he had A1 vision, even though he always wore glasses. His actual call-up was postponed several times because Hitler's Luftwaffe kept bombing the RAF's records, but his enlistment did happen in 1942; in nice time to sabotage and hasten Harry and Marion's wedding plans. The paper shortages caused by the war also sabotaged their promising professional careers as an artist and a science-fiction author respectively.

After basic training at RAF Padgate and a radio course at Birmingham College of Technology, Harry was posted in February of 1943 to the radio school at RAF Yatesbury. There, he found at least one familiar face—Arthur C. Clarke, the science fiction author and creator of the communication satellite concept, who was universally known as "Spaceship". Arthur Clarke knew Harry as a fellow science fiction fan and J.A.A. member, and as a source of high-quality artwork for fanzines. They had visited each other at their respective homes in Longsight in Manchester and London, and Harry's engagement to Marion was reported in Arthur Clarke's fannish newsletter.

As a fully trained radar technician, Harry was obliged to lead a semi-nomadic life, alternating between permanent postings and trips to help keep the many satellite radar stations working. The Germans continued to launch bombing raids at the whole of the British Isles from occupied territory throughout the war, and radar was one of the essential components of the home defence effort.

In the summer of 1945, with the war in Europe over, the RAF sent Harry to India with other luckless radar techs, which deprived Harry of the doubtful delights of early parenthood. The whole thing seems to have started off as a great adventure, which turned sour when the gang reached India and found that even though the war with Japan was over, they were still required to assemble and operate top secret and temperamental radar equipment. [Pictures available on request, except to foreign spies and members of MI 5.]

In India, Harry discovered the paintings and poetry of Amrita Sher-Gil, who was the inspiration for a character in one of Salman Rushdie's novels. Harry's collection of photographs and his own paintings and sketches all include records of his time in India, and the drawings and paintings have been collected in book form. The machinations of the post-war Labour government kept Harry and his colleagues stuck Out East (where the RAF famously went on strike over the slow pace of repatriation) until well into 1946. But they got home eventually.

Back in civilian life, Harry returned to his pre-war employer, the Anchor Chemical Company in Clayton, Manchester, where he had worked as a rubber chemist. A talented artist, Harry used his skills as a designer and graphic artist to create and organized an advertising department. He continued to play an active part in the world of science fiction fandom. Two more sons, William then Robert, arrived to join Philip before the first half of the 20th century ran out.

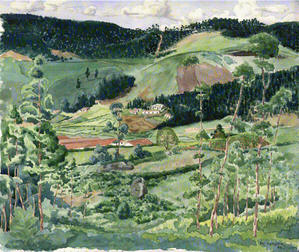

A new job as Advertising Manager at Redfern's Rubber Works in Hyde (1949-58) prompted a move from Manchester to Romiley in 1954. Harry spent the next 54 years in Romiley, where he co-founded the Romiley Fan Veterans & Scottish Dancing Society [Scottish dancing was Mrs. Turner's hobby and not something which Mr. Turner would ever have done!] Romiley was also handy for walking expeditions in the Peak District. Or ‘trudging', as his less willing offspring termed it. Harry was also active in Romiley's cultural life; he was a member of the Beeches Art Group and a popular performer at Romiley Music Group. A new job as Advertising Manager at Redfern's Rubber Works in Hyde (1949-58) prompted a move from Manchester to Romiley in 1954. Harry spent the next 54 years in Romiley, where he co-founded the Romiley Fan Veterans & Scottish Dancing Society [Scottish dancing was Mrs. Turner's hobby and not something which Mr. Turner would ever have done!] Romiley was also handy for walking expeditions in the Peak District. Or ‘trudging', as his less willing offspring termed it. Harry was also active in Romiley's cultural life; he was a member of the Beeches Art Group and a popular performer at Romiley Music Group.

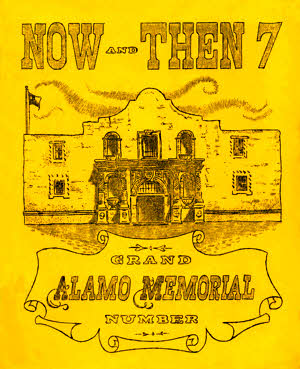

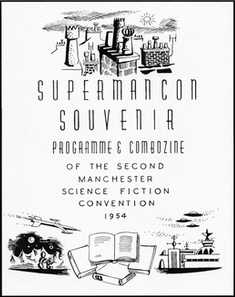

1954 was a big year in the world of SF fandom in the North West of England; the year of the Supermancon (for which Harry produced the souvenir programme), which was billed as "The biggest fan convention of the year". It was also the year when Harry began to publish a new fanzine, Now & Then, with the help of his school friend Eric Needham, a fellow member of the Manchester Interplanetary Society and another refugee from the RAF. Eric Needham, the creator of the now legendary and much imitated Widower's Wonderful range of products, is well remembered in SF fandom circles as the author of fascinating flights of fancy.

Harry's final career move was to the Manchester Guardian and Evening News. His inquiry about the cost of a classified advertisement when he was seeking a change of job caught the attention of the Advertisement Manager, who passed Harry's details on to the Advertisement Director. Harry was recruited once problems of office accommodation had been sorted out and they had somewhere to put him! He became manager of the Advertising and Promotion Department at the Evening News and when he moved again, it was with his department in August 1970 from the old building on Corporation Street to new offices on Deansgate. Harry's final career move was to the Manchester Guardian and Evening News. His inquiry about the cost of a classified advertisement when he was seeking a change of job caught the attention of the Advertisement Manager, who passed Harry's details on to the Advertisement Director. Harry was recruited once problems of office accommodation had been sorted out and they had somewhere to put him! He became manager of the Advertising and Promotion Department at the Evening News and when he moved again, it was with his department in August 1970 from the old building on Corporation Street to new offices on Deansgate.

Harry drifted out of science fiction fandom at the end of the 1950s (gaffiated, to use the technical term). He was drawn back in the 1970s and re-established his reputation as one of the top artists in the field, particularly with the work done for Lisa Conesa's award-winning zine Zimri at a time when he was exploring the possibilities of silk-screen printing. He also became a valuable source of memories for Rob Hansen, author of the part-work THEN, and others involved in recording the early history of science fiction fandom.

Harry was a grandfather three times over when he retired in 1985. Robert and his wife Christine had added Paul, Laura and Michael to the Turner clan. Harry continued to help out at the marketing studio of the Evening News with freelance work and advice, and he was involved in the launch of AM Weekend, the temporary answer from the Evening News to the rash of "free sheets", which were diverting advertising revenue from proper, paid-for newspapers. He also did freelance work for local newspapers as far afield as Bolton. Harry was a grandfather three times over when he retired in 1985. Robert and his wife Christine had added Paul, Laura and Michael to the Turner clan. Harry continued to help out at the marketing studio of the Evening News with freelance work and advice, and he was involved in the launch of AM Weekend, the temporary answer from the Evening News to the rash of "free sheets", which were diverting advertising revenue from proper, paid-for newspapers. He also did freelance work for local newspapers as far afield as Bolton.

Harry was a serial buyer of jazz and classical records; his particular favourites were Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker and Dave Brubeck on the jazz side, and Sibelius, Stravinsky, Prokofiev and a variety of less well know composers (such as J. N. Hummel) on the classical side. He founded the Thelonius Monk Appreciation Society and he decided that his collection of jazz recordings, books, etc. deserved the title: Romiley Jazz Archive. As an active member of Manchester Jazz Society, he gave regular talks to share his expertise and his music collection.

Even with both halves of a pair of semi-detached houses available, there was never enough room for sufficient bookcases to house his swelling book collection, which featured many examples of the dreaded GUP (Great Unread Pile of books). Harry read extremely widely, taking in subjects as diverse as mathematics, the history of art, modern & contemporary art, ancient civilizations (particularly the Maya), Eastern European literature, contemporary fiction, music (classical & jazz), science and its philosophy, astronomy and space exploration. The presence of all sorts of weird and wonderful volumes in the collection, in addition to a wealth of more conventional reading material, won him a reputation for knowing something about just about everything.

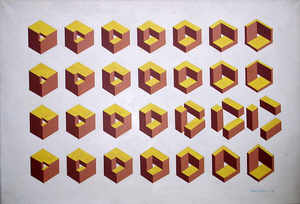

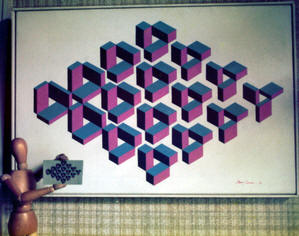

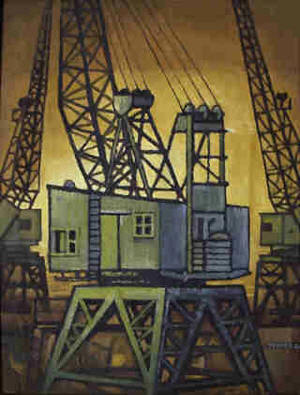

Harry's expeditions into the field of abstract art led to experiments with elements of business charts from his working life, which he turned into paintings in the 1960s. He was also interested in the graphics of perceptual anomalies, influenced by the work of Josef Albers. His exploration of inherent visual deficiencies in the isometric system of drawing led to his development of the "Triad" and the creation of his own niche in the world of impossible objects. Harry was elected to membership of the Society of Modern Painters in 1976 and he eventually achieved international recognition with his Triad designs, some of which found homes in science fiction fanzines courtesy of editors in search of something new and different.

He is the author of Triad Optical Illusions and how to design them, which was published by Dover Publications of New York in 1978, and reissued in 2006 as a colouring book. Harry's draft of a second book of designs for colouring was taken to completion by Farrago Books in 2013.

The Triad is an "impossible figure" formed by grouping three identical shapes round an equilateral triangle.

"Front" and "Rear" Views

Such figures may be similarly linked to produce more complex anomalous figures:

"Front" and "Rear" Views

Further, since the equilateral triangle network, on which the isometric system of drawing is based, is a regular two-dimensional tesselation, Triad figures may be extended indefinitely on the plane to produce paradoxical patterns, reminiscent of geometrical Islamic art.

|

.

An Open University Maths foundation course in the 1970s led Harry to explore the artistic possibilities of geometric paradoxes, geometric dissections and the Fibonacci series. Harry also revived his interest in science fiction fanzines during this period, winning an award for one of his cover designs for Zimri; but clouding cataracts dimmed that interest. In his late fifties, the artist found himself unable to see well enough to paint and draw, to work on his publishing contracts, and to read or watch television. Paradoxically, photography was about all that he could manage with the right equipment.

Following somewhat less than perfect, vision-restoring operations, he added serious stamp collecting to his list of interests, concentrating on the Soviet period in Russia, pre-World War II Germany and the German states, and the German Democratic Republic. He applied his talent for researching a new interest thoroughly to the soaring postal rates of the inflation period, and turned a section of a stamp collection into a work of scholarship. He also went back to the Open University for courses on art—he had actually managed to work through one course in a state of severely diminished vision, having booked it before being told that his first cataract operation would be postponed for 5 months.

Harry began to study Russian seriously in 1986, taking a course run by the National Extension College, Cambridge, and following it up with language courses on audio tape, cards and books. He had already encountered the mysteries of the Russian alphabet through an interest in Russian graphic art during the early Soviet period, and his new knowledge was useful in organizing his Russian/Soviet stamp collection, and layout work for the British Journal of Russian Philately and books created by fellow members of the British Society of Russian Philately.

An expert typographer, Harry was drawn into the world of computers in his seventies in order to design booklets and magazines for friends. These were jobs which he had done manually in the era of Letraset for the likes of the BJRP and the Wyndham Lewis Society. Harry grew to appreciate the convenience of being able to print proofs and make design changes on the spot and he became an essential ally of, and designer for, former Evening News colleague Steve Sneyd's publishing outlet, the Hilltop Press.

He also used his computer to create vast lists of his LP, CD, book and stamp collections, for recycling versions of his pre- and post-war fanzines, and for producing memoirs in booklet form about his time in India with the RAF, his experiences in the world of science fiction fandom and anything else which inspired him, like a cruise to watch the 1973 total eclipse of the sun. The expertise gained in writing classes run by Jim Burns at the extramural department of Manchester University in the early 1990s helped him to polish early versions of memoirs, which had been published in various SF fanzines in the 1970s.

A stroke in his 85th year wiped out most of his memories of his fannish years—a source of great regret to Harry—and his health declined in his final two years. But he took along an often irreverent sense of humour on his trips to hospital, including the final one. When told that a nurse wanted to take his blood pressure, he was still able to come back with: "Where do you want to take it?"

Harry and his wife, Marion, did a pretty damn good job of raising their family, they were very tolerant of the eccentricities of their three lads and they were always a source of inspiration and encouragement. In Harry's case, the final verdict on his life has to be job done, and job well done.

We are now in an age when memories of someone like Harry Turner can endure in small but interconnected pockets on the World Wide Web. Few of us leave behind such a wealth of material, visual and written, to illuminate both the author's own life and those of the people he encountered; particularly the creators of science fiction fandom. So "gone but not forgotten" has never been more true for the likes of The Grand Old Man of British Science Fiction Fandom.

Harry Turner, graphic designer and painter, has exhibited at the following Group Exhibitions:

| 1948 | Midday Studios, Manchester |

| 1950 - 1960 | Beeches Art Group, Romiley |

| 1962, 1967, 1969, 1970, 1973 | Local Artists, Stockport Art Gallery |

| 1967 & 1971 - 1974 | Manchester Academy of Fine Arts |

| 1968 | Arts Council Gallery, Belfast, 4th Open Painting Exhibition |

| 1969, 1971 | SLADE Exhibition, Salford |

| 1970 - 1979 | Stockport Art Guild |

| 1972 | John Moores Liverpool Exhibition 8 |

| 1976 | Society of Modern Painters, Salford Art Gallery |

| 1986 | Impossible Figures, Museum Hedendaagse Kunst, Utrecht |

| 1987 | Unmöglichen Figuren, Stadtmuseum, Ratingen, Düsseldorf |

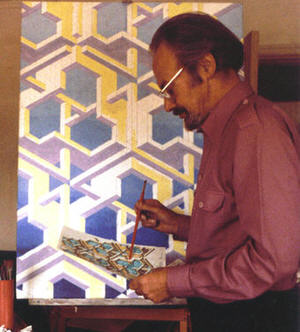

The man himself . . .

Harry Turner was a fan of Krazy Kat [George Herriman], Peanuts [Charles Schulz], Calvin & Hobbes [Bill Watterson] and Bogart [Peter Plant], the artists Frank R. Paul, Elliott Dold and Eric Fraser, TV snooker from the early days (he once met Steve Davis at Piccadilly station in Manchester), The Invaders, Star Trek: The Next Generation (he was especially amused by Capt. Picard forever pulling his jumper down), Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Babylon 5, The Last of the Summer Wine, Monty Python's Flying Circus, Fawlty Towers, the Time Team [especially Prof. Mick's striped jumpers], Horizon (before it 'went off' and deserted real science), the Discworld books of Terry Pratchett, Ancient Egypt, the Maya, the works of Charles Fort, the stories of Mikhail Zoshchenko and H.P. Lovecraft, Thorne Smith, Stephen Leacock, the Good Soldier Svejk, playing chess, jazz, especially Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk & Dave Brubeck, Classical music, especially Jean Sibelius, Johann Nepomuk Hummel & Russian composers, Halle Concerts, electronic music, Leon Theremin and his electronic musical instrument, poetry (especially in its more exotic forms), Martin Gardner, optical illusions, mathematics, Professor Richard Gregory, fractals, space flight, airships (especially when used to explore the Arctic), Richard Feynman, Scientific American magazine, (solid) rice pudding (no nutmeg), slices of proper bread pudding, white wine, gardening, DIY, fish & chips, and Campari, and like his father, he was a great one for gadgets, some of which actually worked!

Harry Turner was a man of many ideas and enthusiasms, which he enjoyed sharing with others. He could turn his hand to most practical matters, including home printing with a duplicator, hi-fi equipment and all types of construction work, including building custom items of furniture. He was also a keen gardener and garden sculptor in his younger days, and he became a master of calligraphy as a means of improving his handwriting. He made the transition from electric typewriter to computer plus laser- or inkjet-printer with great success, extending both his desktop publishing activities and his range of graphic art talents. And maybe he could have been a rocket scientist if he had followed his early inclinations!

|  © RFV&SDS, MM23. © RFV&SDS, MM23.

|

|  |

A new job as Advertising Manager at

A new job as Advertising Manager at  Harry's final career move was to the Manchester Guardian and Evening News. His inquiry about the cost of a classified advertisement when he was seeking a change of job caught the attention of the Advertisement Manager, who passed Harry's details on to the Advertisement Director. Harry was recruited once problems of office accommodation had been sorted out and they had somewhere to put him! He became manager of the Advertising and Promotion Department at the Evening News and when he moved again, it was with his department in August 1970 from the old building on Corporation Street to new offices on Deansgate.

Harry's final career move was to the Manchester Guardian and Evening News. His inquiry about the cost of a classified advertisement when he was seeking a change of job caught the attention of the Advertisement Manager, who passed Harry's details on to the Advertisement Director. Harry was recruited once problems of office accommodation had been sorted out and they had somewhere to put him! He became manager of the Advertising and Promotion Department at the Evening News and when he moved again, it was with his department in August 1970 from the old building on Corporation Street to new offices on Deansgate.

Harry was a grandfather three times over when he retired in 1985. Robert and his wife Christine had added Paul, Laura and Michael to the Turner clan. Harry continued to help out at the marketing studio of the Evening News with freelance work and advice, and he was involved in the launch of AM Weekend, the temporary answer from the Evening News to the rash of "free sheets", which were diverting advertising revenue from proper, paid-for newspapers. He also did freelance work for local newspapers as far afield as Bolton.

Harry was a grandfather three times over when he retired in 1985. Robert and his wife Christine had added Paul, Laura and Michael to the Turner clan. Harry continued to help out at the marketing studio of the Evening News with freelance work and advice, and he was involved in the launch of AM Weekend, the temporary answer from the Evening News to the rash of "free sheets", which were diverting advertising revenue from proper, paid-for newspapers. He also did freelance work for local newspapers as far afield as Bolton.