The ship is a labyrinth

M/v MONTE UMBE, 8900 tons,

Naviera Aznar SA, Bilbao

a multi-layered maze

A deck, main deck, promenade deck, sun deck

narrow corridors stretch endlessly

past cabin doors--numbered and named,

officia, private, prohibito,

with the occasional blank face (senoras)

or mustachioed face (caballeros)--

and open at intervals on to a deck,

(but which deck?)

lead unexpectedly to open areas

and wide stairways

curving up to the sun deck

or, invitingly,

down to a capacious dining room.

With practice, passengers become familiar

with the shortest route between any

two points.

The labyrinth begins to yield some

of its secrets.

You identify rallying points:

the information centre

the Marina and Les Robles lounges

the swimming pools

the cinema, Verandah bar

Maxim's night club...

The memory stores data, computes

guides your feet.

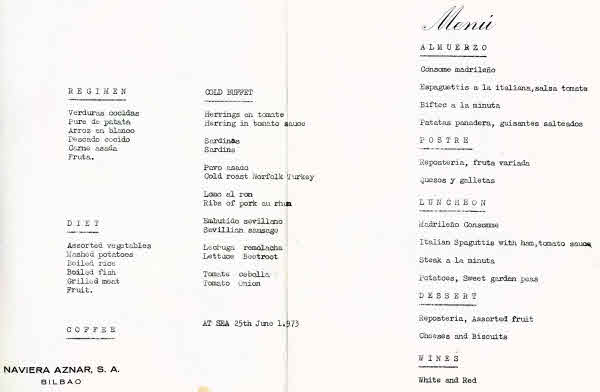

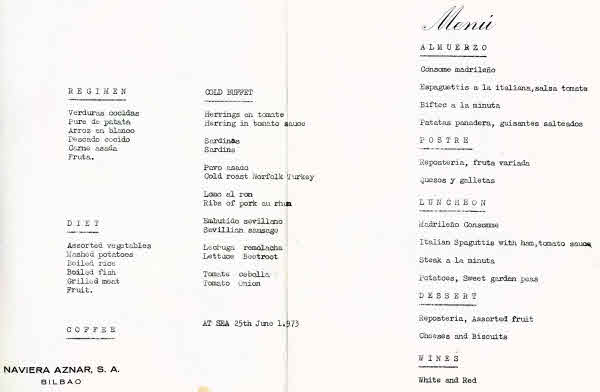

■ It's Monday 25 June. We're somewhere off the coast of Portugal, or even further south. It's 7.25 am. I woke early, and at 7am precisely heard the steward delivering tea to the cabin opposite. On our first morning we'd been roused by a violent knocking on the door at what seemed an ungodly hour, and sternly refused offers of tea then, and for the rest of the voyage. The morning light penetrates our window, a bright square moving leisurely up and down the wall opposite as the ship slowly rolls through the swell.

Odd how large the cabin seems when viewed from the bunk. On arrival it looked cramped, claustrophobic... but there's somewhere to stow all our possessions out of sight, the steward keeps it all neat and tidy, and now, peering round the corner of the wardrobe unit, there seems space enough.

The vast four-compartment wardrobe, with hanging space and multiple drawers, occupies the wall opposite the door, with a bunk along the cabin walls on either side. At the head of each bunk is a convenient recess for odds and ends, like books and specs, with the steward's bell and a switch for the bedlight. Between the wall and the door is the washbasin with an impressive array of glasses, flasks, and trays all individually clipped to the wall.

A murmur of conversation seeps through from the cabin behind us. Elsewhere something is vibrating softly. Can't be the cabin door as I folded an envelope and wedged it in position last night to stop it dancing to the insistent rhythm of the ship's engines. Must be one of the wardrobe doors. But there is a subtle shift in the vibration that hits the resonant peak of some other part of the structure to set it dancing in its turn...

■ The ship's shop is quiet. The señora in charge speaks little English, but we do our best to communicate.

I point.

Sombrero?

I nod.

Par hombre?

I nod again then unbend and try out my limited Spanish.

Cuanto?

We establish the price as 62 pesetas, and so I acquire my sombrero blanco par hombres.

Marion says I look a right character in it, but it provides welcome relief to my sun-scorched forehead.

■ What colour is the sea? Well, it's not blue--it must be indigo.

Always wondered what indigo looked like, lost between blue and violet. Guess this must be it. But as we slide further into the Bay of Biscay, there is a subtle change to pure ultramarine. The sun blazes down from a clear sky. The ship cuts through the calm sea bringing a pleasant fresh breeze. Lurking in a quiet oasis on the foredeck, between hoists and gantry, away from the regimented deckchairs, I can stretch out on a towel and soak up the ultra-violet. I don my sombrero blanco: very elegant. I rub myself down with oil and quietly fry.

Periodically, the surrounding chatter and pervasive rumble of the engines are punctuated by a chime of bells heralding a message over the amplifier system. Prosaic requests, instructions, pleas, exhortations in English...

"Will all passengers who have not collected passports please do so forthwith; thankyou..."

"Will Miss Somebody-or-other please report to the information desk; thankyou..."

"Mr. Mumble-mumble will be franking envelopes and postcards with the special eclipse cancellation stamp between four and four-thirty mumble mumble; thankyou..."

Then there are the messages relayed in Spanish: seductive, sheer poetry, reminiscent of those radio messages in Cocteau's film Orphée, fragments of surrealist poetry from another plane of existence; occasionally the firm voice of authority, brief and brutal, its eloquent syllables passing on secret instructions for the crew's ears only:

"All those assigned, report to the dining room and take up allotted positions--when the passengers appear, shoot..."

"All stewards will creep into the passenger cabins tonight and rape and murder..."

"The ship is sinking--abandon ship and to hell with the passengers!"

But the voice of head waiter Mariano de la Huerga interrupts, inviting us to over-indulge...

"Will all passengers for the first sitting make their way to the dining room, where lunch is being served. Thank you."

We're on second sitting. I apply another coat of soothing oil and turn over.

We join stargazers on deck that evening, just after ten o'clock, to be rewarded with a view of Skylab drifting across the heavens before disappearing into the mists. I find there's a knack to focusing binoculars on the moving point of light while compensating for the steady roll of the ship.

■ It's Wednesday 27 June. We are at Las Palmas. Five coachloads of enthusiasts leave the Monte Umbe early in the morning, taking the coast road through residential developments, ferro-concrete frames sprouting from areas cleared out of dusty lava rock, then past the airport, in time to see Concorde nosing its way down to the ground to prepare for its eclipse flight to Fort Lamy in Chad, Central Africa.

The dry countryside, resting between tomato crops, is spiked with teepees of canes, all dusty browns and ochres, and an occasional green patch of bananas. Eyes are battered by blatant advertising at every turn of the road--posters, signs, constructions--and even carved out of the dark dusky mountainside in white: PIGALLE DISCOTHEQUE & NIGHT CLUB. Then we are through Mas Palomas and on the way to the tracking station, an artificial grassy oasis in the parched wilderness.

This is one of the eleven ground installations, a ship and several aircraft that make up the Manned Space Flight tracking network, providing NASA with data and communications to control space flights, as well as receiving information from scientific experiments set up on the moon by the Apollo astronauts. When we arrive, some of the staff are making adjustments to the large dish erected outside the station. The promised tour of the building proves somewhat perfunctory: they don't seem organised to deal with visitors and the Spanish technician is not happy trying to explain the functioning of the equipment in any detail. But we do the rounds, see the gear controlling the position of the main antenna and receiving data; see the computers, fed directly from the VHF radio signal antennas, and recorders taping information from satellites as well as that originated in the station, and all exchanges between Houston, Goddard, and manned spacecraft.

At the entrance gate of the station there's a small observatory and spherical-shaped building--

the Solar Particle Alert Network Observatory. It gathers data from solar flares and radiation using

optical and radio telescopes, and other recording devices. We don't get in there, alas.

The tour then takes us to the centre of the island, and the aspect becomes greener and more

pleasant. Some of the larger villages we pass through look relaxed and civilised after the frenetic

development along the coast; houses set in extensive gardens, places in which to enjoy life at a

reasonable pace, in the sunshine away from the rat-race. We pass by them all to start the long

climb to Tejeda.

The driver seems to heave the bus physically round the hairpin bends. ["Driver he is very

skilled and family man" announces our guide "So you are safe!"]. Fortunately there are no

coaches coming down and we soon reach the top, cleared to give parking space for several

coaches with the inevitable souvenir shop on the peak.

There's a marvellous aerial view of the

whole island, dark shadows of clouds drifting over the landscape, with Las Palmas clearly visible

to the north. And immediately below the peak is the vast crater of an extinct volcano, now eroded

and under cultivation, but still impressive from this vantage point.

When we eventually arrive back at the ship it is almost dinner time, but we dash to enjoy a

brief evening walk on the tiled pavements of Las Palmas. It seems very noisy, traffic zooming

along at a fast lick, impatient horn blasts, the screeching of punished tyres...

Perhaps it is just the

contrast after the relative peace and quiet aboard the ship. But it is good to walk on dry land

again, to stroll through the city amid the bright lights, hear waves of explosive conversation from

the small bars as we pass by, to do some window shopping--the only shops still open are those

flogging optical and audio equipment--and wonder how it will all look in tomorrow's sunshine.

We return to the ship, enjoy a lively concert given by the folk group Pueblo Canario. Can't

resist buying one of their records; hopefully it will sound evocative when played back home.

■ Thursday 28 June. We rise early to continue our exploration of Las Palmas since the ship sails at 1 pm. It's cloudy when we leave the harbour, the sun lurking behind the haze, but we take the

cine camera and hope it will clear. We wander round the Castella de la Luz and gardens, visit the

Fruit Market and marvel at the sheer variety of exotic fruits on display.

Find a post office, a modest establishment lurking behind large wooden doors, indentifiable only by a scruffy enamelled correos sign above a slot in the post between the doors. [I hope the letters we

optimistically cram in it are delivered!]. Inside a series of little windows with signs indicating

the business transacted; a long queue outside the stamp window and a hectic discussion every

time a new customer moves up and sticks his head through the window.

My request for 5-peseta stamps causes a slight delay since a new sheet has to be folded meticulously and torn into strips of five stamps, an operation carried out with great deliberation by the official, seemingly oblivious to the growing queue forming behind me. Then a further delay when he has to seek some 8-peseta stamps [obviously not in general demand as I am pleased to get some commemoratives, and only notice later that they are Christmas 1972 issues!].

We emerge into sunshine. I rush round wielding the cine camera in a frantic effort to make up for lost time, before we return to the ship.

Promptly at 1 pm the Monte Umbe departs Las Palmas. In almost no time at all, there is only an outline of buildings on the horizon, with the mountains beyond, all shimmering in the heat haze. And then nothing. Just the sea, stretching to the horizon.

And we are off to see the eclipse.

■ All around us enthusiasts are setting up and testing their equipment. On one side of the deck, Patrick Moore, a giant teddy bear in a tent-like shirt and baggy trousers, with a tiny shiny straw hat perched on his bonce, is about to launch into the umpteenth take of an interview with someone he's known for fifteen years (he keeps telling us), but alas, the person concerned persists in turning away from the camera and mike to explain his set-up. The director yells "cut" and a confab ensues, then the rigmarole starts all over again.

Patrick looms into the camera view and repeats his opening spiel after the board has clapped down on "take 19"... and it goes wrong again! Ah well, if this never makes it on to the BBC TV screen, at least I've got it on film...

■ Up on deck in the dark tropical evening groups of astronomers are star gazing. I find I am

distracted by the smoke from our funnel, illuminated by navigational lights high up among the radio mast and radar gear, and realise that the string of fairy lights that blazed the whole length of the ship while we were at anchor at Las Palmas, has been extinguished in deference to the observers on the foredeck.

I hope it doesn't mean we are a navigational hazard--but with lights

streaming out from all the decks below and the aft sun deck decorated with coloured lights, I guess we must be visible for miles.

I lean over the side, watch the intriguing waveforms created by our speedy progress, seething white foam-crested ever-changing patterns perpetually racing away from the bows, collapsing against the sides of the ship, vanishing into the outer darkness. Further out, occasional patches of phosphorescent foam are thrown up and race along with us, at the periphery of the light cast on to the surface.

■ Is it really a week since we set out? There has been much talk among the experts of the

problems of ensuring the ship is in the right place at the right time tomorrow (and a short prayer that there will be no morning haze to obscure the view).

An American expert, Mr Baumgartner, held forth about the phenomenon of shadow bands, laconically described the difficulties of observing them and dismissed all theories put forward to explain them. Marion found this interesting, but I had to admit that he lost me during the talk. So I adjourned and went sunbathing. Followed by a shower, then a refreshing Campari-soda with peach juice and lots of tinkling ice. Yes, this is a lazy day, to be enjoyed before the Big Event!

■ It isn't every day that one views a total eclipse and then sails into Nouadhibou, main port of

the Islamic Republic of Mauritania. Just one day.

Like today, Saturday 30 June 1973.

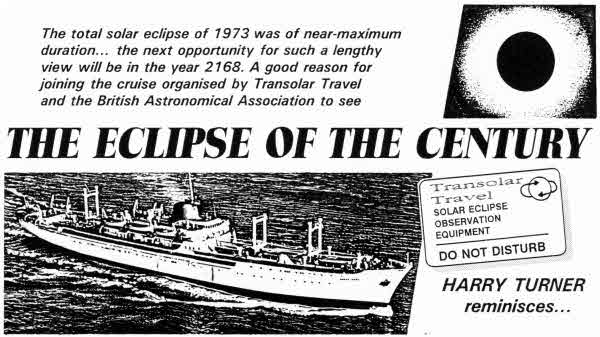

The cruise brochure promises that we are here to witness an outstanding astronomical

event--an exceptionally long total solar eclipse. Not until the year 2186AD will an eclipse of

similar duration occur, which is the best reason in the world for our presence here right now.

The

shadow of the moon will originate near the borders of Brazil and Guyane, travel across the

Atlantic Ocean and the Cape Verde Islands, pass over Mauritania and the African continent to

the Indian Ocean. The maximum duration of total eclipse will be seven minutes plus.

The plan

is that we sail down to a point in the centre of the 150 miles-wide shadow of the moon, and

heave-to, so the ship becomes a floating observation platform.

We're two of many up before dawn, full of eager anticipation, roaming the dew-covered decks

seeking a vantage point. The well-equipped groups and enthusiasts have already monopolised

the fore deck, staked out claims with apparatus set up and waiting. But there's plenty of room at

the rear where the view is clear of obstacles.

It seems strangely still, with no detectable engine

vibration: the ship is virtually motionless, with engines merely ticking over to provide power and

counter the movement of the water. We mark out our chosen observation spot, watch the sun rise,

a pale disc in the haze on the horizon, then descend in search of breakfast.

In the dining room the talk centres on two topics: are we in the best position to get the

maximum period of totality? and will the haze disperse or get worse and interfere with viewing?

The liner Canberra with a party from New York was due to rendezvous with us and pass on data

from weather satellites, but there has been no contact so far. Fears are expressed that she has

departed elsewhere in search of clearer weather.

We return to our station, sort out filters and cameras, as the sun climbs slowly in the sky. The

haze has not cleared but at least seems no worse. The deck fills gradually with preoccupied

observers making last fiddling adjustments to equipment. The minutes stretch: we wait,

impatiently.

There is a stir as the time for initial contact approaches. Marion passes me a filter, through

which the sun appears as a pale disc. At 9 hours 21 minutes GMT, partial phase begins: the moon

takes a first nibble from the top of the solar disc, leisurely begins to eat its way down. There is a stir as the time for initial contact approaches. Marion passes me a filter, through

which the sun appears as a pale disc. At 9 hours 21 minutes GMT, partial phase begins: the moon

takes a first nibble from the top of the solar disc, leisurely begins to eat its way down.

The disc

becomes a crescent with the cusps above. As it does so we are conscious of a pervading gloom:

damn, the haze must be getting thicker. The temperature drops appreciably then realisation comes

that this darkness is due to the progressive elimination of the sun's rays.

The sea is calm: it's so

quiet I can hear the waves lapping and slapping on the ship's side, above the faint murmur of

conversation and a modulated radiophonic tune gently whistling from some nearby gear.

It all happens at a deliberate pace. We view the progress of the eclipse through filters until

there is the slimmest outline of the solar disc left. Then, just as the moon completely blocks out

the sun, there is a sudden silent explosion of light.The sky turns black, day becomes night: the

brilliant solar corona flares around the obscuring disc of the moon, an exquisite ring of pearly

radiance, a giant catherine-wheel suspended in space, its cold fiery faery writhing light bright

enough for me to read the settings on the camera. We shiver as the temperature drops

appreciably. I catch a glimpse of Marion, wide-eyed, staring at the spectacle in the heavens, am

tempted to comment but hold my tongue in the face of that rapt gaze, am lost myself...

It lasts well over the full six minutes we'd been promised--a compliment to the navigational

skills of Captain Vincente Mirallave in placing us on the right spot in that waste of ocean--as

long as a lifetime and yet still not long enough. Then the rim of the sun appears above the moon,

a quick sparkling of Baily's beads round the breaks in the lunar mountains, a sudden flash that

heralds the end of totality, a warning that naked eye viewing is at an end.

It happens so abruptly that everyone seems surprised--the corona vanishes, the sun is shining

again, we are washed with light, colour and warmth. All the pent-up emotion of the past minutes,

a unique experience shared, erupts as a sudden burst of conversation. Then, an odd gesture, a

spontaneous round of applause. The scientists among us relentlessly record the moon's passage

to the bitter end. We linger awhile, watching through filters, still too dazed by the spectacle to

talk.

■ Later that afternoon, relaxing astronomers are momentarily entertained as a small boat draws

alongside and a Mauritanian pilot, with a great show of athleticism, grabs a lowered rope ladder

and climbs aboard. Then a first glimpse of Africa: the Cap Blanc promontory, outlined against

a roseate dust cloud masking the horizon. As we sail into the Bay of Levrier fine sand envelopes

us, sifting down shirt necks, invading hair, gritting teeth.

Majestically the Monte Umbe draws

alongside an almost deserted quay, dwarfing the fishing vessels with their green crescent-and-star

flags. A lone figure, tall, dark, resplendent in a flowing blue robe, hefts a video camera and

gravely films the tourists busily photographing him. It seems we are the first pleasure cruiser ever

to put into the workaday port of Nouadhibou, and likely to be the last. Hence the interest of

Mauritanian TV in recording the event.

■ A press release by the Secretariat General à L'Artisanat et au Tourisme of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania says, in part:

"The port of Nouadhibou is suitable for all large vessels and has extensive loading and

unloading facilities. However, it must be noted that continuing transport to Nouakchott, Akoujit,

Atar, etc., can be effected only by air or sea, tracks being virtually non-existent... It must be

considered impossible to reach any other town in Mauritania overland from Nouadhibou. A

journey along the beach is particularly dangerous because of high dunes and tides."

In other words, Nouadhibou is a dead end.

■ When our expedition was first mooted, the intention was to sail to the Islamic Republic of

Mauritania and observe the solar eclipse from the interior. The Mauritanians, when advised of

these plans, politely pointed out that communications in the northern desert, over which the

eclipse shadow would pass, were non-existent; that Nouadhibou, the iron-exporting port, while

able to accommodate a ship the size of the Monte Umbe, was virtually isolated from the rest of

the country; that day temperatures in the region exceeded 100F during July and, worse, that sand

winds from the Sahara would not only obscure observations, but gently and effectively scour and

ruin all delicate optical and mechanical parts of unprotected instruments.

There was a rethink. Despite the problems, it was decided to view the eclipse out in the

Atlantic. A few diehards shook their heads at the wild notion that the ship could provide a stable

platform for worthwhile observations: they decided to leave the cruise at Las Palmas and fly on

to Africa, where their equipment had already been transported, despite the misgivings of the

Mauritanian authorities. So, fresh from a spectacularly successful view of the eclipse at sea, we're

now here to pick up the returning members from this land expedition.

After a snatched meal, an enthusiastic band descend to the quay, collect at a small public post,

where harassed gendarmes struggle to decipher passports and scrawl out the strange names on

24-hour passes guaranteeing "safe conduct". There's a currency exchange at the post: we'd been

told that the going rate was 500 African francs to the £, but our advent coincides with a national

revaluation to a new currency, and our sterling is exchanged for freshly printed and minted

ougiya. We wander a short way in the growing dusk along a poorly lit gritty road that turns

abruptly to run straight on into darkness. The wind veers, bringing an overpowering whiff from

the nearby fish-drying factory.

We turn back to the comforts of the ship. Enough is enough: we can wait to do our exploring

on the morrow...

■ It's Sunday 1 July 1973. A hastily arranged scratch tour can only cater for a hundred or so

passengers. We'd arranged with the couple in the neighbouring cabin to share a taxi, make an

early start and return for lunch, then find that the tour has not only hired both available coaches,

but the whole of the local taxi fleet.

Fortunately, as we set out before the main party is ready, we

are able to bribe the driver of an ancient taxi to take us as far as the market, which we're told is

the heart of Nouadhibou. He belts down a long tarmac strip, swerves on to a stony track covered

by drifting sand, and after some complicated manoeuvres there we are. The driver grabs his

money and promptly rattles back to the quay.

The sun is still low on the horizon, but the flies are already active. People are setting out their wares at a few stalls; goats wander everywhere, their udders tied up neatly in little bags, scavenging among the waste. A low huddle of undistinguished concrete buildings surround the market; beyond a wooden shanty-town proliferates. Isolated buildings advertise their purpose--here a restaurant, there a 'couture' complete with paintings of trousers on its walls and a sad cartoon of a European suit. Not that any of the inhabitants present wear anything that resembles a suit.

Most of the men favour flowing robes of white or light blue; there are turbanned Arabs, mouths masked against the dust; negroes in long gowns, or lengthy dark jackets buttoned down the front; the occasional worker from the harbour or mines, in slacks, shirt and obligatory hardhat. Women are in traditional Arab dress, dark, concealing, all enveloping, or else the bright patterned robes favoured by the negroes.

We wander round looking at the natives, and the natives, unspoilt by tourism, stare curiously at us. A tentative greeting of bonjour produces shouts of bonjour in reply and some friendly grins. We ask directions to the post-office--French is the get-by language--but our difficulty is in interpreting the directions offered, since the general layout of the buildings seems so capricious.

The only road is the track on which we'd travelled in; the buildings seem to be dumped haphazardly in the desert on either side of this. When a willing youngster offers his services as guide, we snap him up.

Sidi, with the rest of Nouadhibou's children tagging behind at a cautious distance, leads us unerringly through the maze, chattering happily and pointing out landmarks as we progress. A cinema, a modest Catholic church, a broken-down water wheel. We pause to look at this token of a less arid past:

Sidi doesn't seem to know what it was for--he's probably never seen it

working because of the worsening drought that had dogged northern Mauritania in recent years.

The post-office proves a more imposing structure than most, its walls plastered with official posters in French and Arabic, warning the locals of yesterday's eclipse and the dangers of gazing directly at the sun. Intending customers already crowd the doorway, but it seems the postmaster isn't expected for another hour. Rather than wait, we decide to return to the awakening bazaar with our cameras.

Sidi escorts us back; when we pay him for his services we have great difficulty in shaking off the rest of the entourage.

We find business in full swing, people doing their daily shopping, sorting the goods, haggling. Dust settles on garments, bright bolts of cloth, sandals, heaps of fruit and vegetables, cooked foods aswarm with flies despite flailing hands. The insects are everywhere, crawling unheeded on the faces of the children, crowding the eyes of bleating goats.

Muslim women in black robes shout curses, throw handfuls of dust when a camera points in their direction. A slim girl with a baby on her back offers to pose for us, vous donnez un cadeau? We gladly give her a few coins. When others cotton on, start lining up for a group photograph we beat a hasty retreat back to the post-office.

The waiting crowd has grown meantime, restless at the non-appearance of the postmaster. Most want to get money changed because of the currency revaluation; if we only want stamps we're told, there's another post-office further along the highway--take a taxi, we are told. We know there's not much hope of doing that today. But how far, we insist. Oh, about 30 kilometres only... It seems a lot of effort for a few stamps and we abandon plans to send postcards home from sunny Nouadhibou.

In the bazaar, rumours of an influx of tourists have attracted a wave of traders from the surrounding desert, bearing trays of bead ornaments and silver jewelry thin as tissue paper, big round toffee tins with silver and gold trinkets packed in cottonwool, or lugging canvas hold-alls bulging with ethnic wood carvings.

Every visitor from the ship is under seige. Show the faintest

interest in these wares and you are immediately involved in the bargaining ritual: a complicated procedure, with delighted bystanders freely joining in, all in several languages, translating, commenting, advising, warning, as you juggle with four different currencies--African francs, pesetas, pence and the brand-new ougiya.

Only the arrival of a more promising customer can rescue you from the impasse that often results. Despite lapses into complete confusion I do acquire some carvings. But it is hot, noisy, smelly and the flies too aggressive. We wilt... Miraculously a stray taxi trundles up the road, rescues and returns us to the harbour and the peace of our cabin.

We sail from Nouadhibou late that afternoon, simmering in the heat, fine Saharan sand

clinging to sweaty skin, pursued by militant flies and the persistent reek of drying fish. Then

welcome sea breezes cool things down, disperse the insects, freshen the air and make life

bearable again. And we are off to Tenerife. ■

FOOTNOTES TO FANDOM #20...

one of a series of occasional pieces published by the Septuagenarian Fans Association, August 1998

© Harry Turner, 1998. |

There is a stir as the time for initial contact approaches. Marion passes me a filter, through

which the sun appears as a pale disc. At 9 hours 21 minutes GMT, partial phase begins: the moon

takes a first nibble from the top of the solar disc, leisurely begins to eat its way down.

There is a stir as the time for initial contact approaches. Marion passes me a filter, through

which the sun appears as a pale disc. At 9 hours 21 minutes GMT, partial phase begins: the moon

takes a first nibble from the top of the solar disc, leisurely begins to eat its way down.