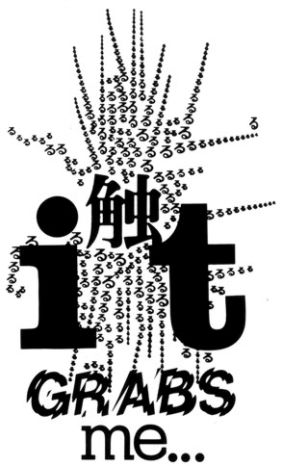

—That’s really great, I have to admit, confronted by Jo’s latest adjunct to gracious living. It’s a large print, a visual poem by the Japanese concrete poet Seiiki Niikuni.

—Well, nobody gets turned on by art so much as another artist, smiles Jo.

We’d been invited to eat at Jo Withisone’s apartment. A privilege doled out to few, Lisa informs me. She filled me in about Jo’s taste in furnishing her penthouse but omitted to mention that the lift would be out of order on the day we called. She’s a writer and poet, pants Lisa as we toil up the stairs, and she’s got a centrefold of Steve McQueen on the ceiling over her bed...

When we finally arrive, Jo’s apartment proves warm and inviting. So does our hostess, looking exotic in something black and close-fitting. I pause momentarily, to take it all in and get my breath back, but Lisa pushes me impatiently over the threshold.

Reed mats and colourful cushions are scattered over the floor; a long, low table stands against a wall dominated by the large print. Simple but impressive—all that Lisa had said, I admire it.

Jo laughs and explains the low-level living as just the result of bad planning. Like, she’d seen this table in a junk shop, decided it was ideal for her new abode, and then after it had been manhandled into the lift and unloaded on to the landing, she found there wasn’t room to manoeuvre it through the apartment door.

The man, jokingly, suggested that the only way to get it in the room would be to saw off the legs. Jo, in desperation, did just that. When the truncated table was installed, she realised that there was no need to buy chairs. An economy that appealed to her.

And the large print really sets the seal on the Oriental-type decor.

— means ‘touch’ and the repetitions of the phonetic symbol means ‘touch’ and the repetitions of the phonetic symbol  show the delicacy of the art of touching, explains Jo, adding hastily, I got that out of the exhibition catalogue. show the delicacy of the art of touching, explains Jo, adding hastily, I got that out of the exhibition catalogue.

—I think it’s fascinating the way he uses the ideograph to create a visual image that’s appropriate to the meaning; a real visual poem, enthuses Lisa.

Jo serves a splendid meal: chicken breasts and mushrooms in sherry sauce, with Mandarin oranges, washed down with hock. She’s puzzled to find the sherry sauce has an unexpected piquancy, but Lisa modestly claims credit for spiking it with gin.

Over coffee and Cointreau we drift back to the subject of art.

—Too few people enjoy direct confrontation with art, I throw out, because they’re content to take it secondhand as reproductions in books, films and slides, and on TV. So much depends on the physical presence of a work of art—its scale and relationship with its surroundings, its material, texture, colour... Reproductions are just filtered viewpoints, a partial and distorted experience.

—¡Pero, hombre! explodes Jo, surely it doesn’t matter what a work of art looks like; if it’s a physical object it’s just got to look like something. But no matter what form it takes, it always begins with an idea. That’s the important thing in my mind. But an idea doesn’t have to be given physical shape—an artist can express herself in any way. If she uses ideas that proceed from ideas about art then they are art and not literature... like Yoko Ono’s advice: ‘Use your blood to paint; keep painting until you faint; then keep painting until you die’. Then there’s her idea of listening to the sound of a room breathing—at dawn, in the morning, in the evening, just before dawn. And bottling the smell of the room at each time as well.

Lisa decides she must try that herself. I hope she refers to the second proposition; the first sounds messy.

—We seem to be round to the subject of conceptual art and back to the presentday confusion about the nature of art, I say. Several artists believe they are already enough art objects in existence and feel no urge to add to the number. So they’ve abandoned the art object and regard anything they do as being art. Personally, I don’t think that’s the answer.

I welcome uncertainty because it leads to constant questioning, experiment, and discovery. And that’s been the driving force of art in this century: a continuing visual debate about what art is. We discard subject matter in the effort to escape the literary associations of the past and to disentangle the image from the words. Now the pendulum seems to be reversing and some artists are bringing back words again, replacing the art object with the documentation of an idea...

—That’s only logical, interrupts Jo.

—Pursue logic to extremes and the result can be nonsense. The preoccupation with documentation logically follows on from the basic idea of action painting—the end product is not so much an art object as a direct record of the artist’s creative processes. Logically, the work may be partly invisible to carry out the artist’s intentions—like Duchamp’s With Hidden Noise, a ball of string with a small object added and concealed inside: or even totally invisible, like Oldenburg’s project for buried sculpture.

Take logic one step further, and the object doesn’t need to be made; the creative act is the proposal itself. I deplore this in a way, yet have to admit that I wish some contemporary manifestations would stop just there. Like the proposal for the Otterlo Mastaba by Christo...

—Who? chorus Jo and Lisa.

—Christo. The guy who goes around packaging public buildings, wrapping up cliffs, and hanging plastic curtains across valleys. His latest project is the building of a mastaba, measuring 60 by 50 metres at the base, and rising to a height of over 50 metres, using 242,945 empty oil durms. He’s actually had a feasibility study carried out on this monument to the oil sheikhs by the Ken R. White Company of Denver, Colorado. Maybe the project is held up by the oil crisis. I hope so.

—Reactionary, mutters Jo.

—It may sound a horror to you, chips in Lisa, but don’t forget that Duchamp, all his life, tried to find an unaesthetic object, yet all his ‘found objects’, his ‘readymades’—the urinal, the bicycle wheel, the bottle rack—became regarded as aesthetic objects just because he forced people to look at them outside their functional role.

—Right. If I says it’s art, it is art. And people are still finding out that very thing. There’s the N.E.THING COMPANY, formed by a group of artists in Vancouver during the 60s, who executed a series of landscapes by the simple process of putting up signs along country roads. First came the warning: YOU WILL SOON BE PASSING BY A 1/3 MILE N.E. THING CO. LANDSCAPE: START VIEWING. A little further on the motorist was informed: YOU ARE NOW IN THE MIDDLE OF THE N.E. THING CO. LANDSCAPE. And finally: STOP VIEWING.

I wonder how many people became aware of a landscape at which they really looked for the first time... Then there were Marjorie Strider’s street pictures—she put up 30 empty picture frames along a street to create ‘instant’ art works, drawing the attention of people to different aspects of their environment. She did it twice in different streets but never discovered how successful she was, since most of the frames were stolen by passers-by.

Seth Siegelaub is another believer in logic who started from this assumption that people rely largely on the secondary formation of reproductions of works of art and finished up organising the first art exhibition to exist in catalogue form only. He asked artists to provide a written description of the work they would have put in the exhibition, published the information in catalogue form, and that was it. No need to bother with the actual exhibition.

The catalogue was enough—certainly enough for those who would not have travelled in to see the show anyway! An artist with an idea will always find a way of expressing it, but I subscribe to the view of American art critic Harold Rosenberg that the artist is the product of his art.

Most artists develop ideas through unfocussed play in their chosen medium. Most of the art of our time has arisen out of ideas about art: cubism out of Cezanne’s methods, action painting and much abstract expressionism out of the work done by Monet in his last years when his eyesight was failing. It is these accumulated insights, conflicts and disciplines of painting, of poetry, of music, that provide the artist with the means of self-development. And surely art’s value today is that it gives the individual breathing space to realise himself in the face of increasing communal pressures and the restricting mass-behaviour of our society.

—You don’t convince me, comments Jo when we prepare to depart. As someone said: One word is worth one-thousandth of a picture.

Lisa grins appreciatively at that. I feel outnumbered... ■

The artistic projects mentioned are all genuine. And they’re detailed, among others, in a book by Lucy Lippard: SIX YEARS: the dematerialisation of the art object 1966-1972. Recommended reading!

from Zimri 7, January 1975 |

means ‘touch’ and the repetitions of the phonetic symbol

means ‘touch’ and the repetitions of the phonetic symbol  show the delicacy of the art of touching, explains Jo, adding hastily, I got that out of the exhibition catalogue.

show the delicacy of the art of touching, explains Jo, adding hastily, I got that out of the exhibition catalogue.