| With the RAF in India #5 | HISTORY Page | Obituary Page | |

| |||

St. John's Convalescent Hostel in Bangalore is run by the Red Cross in the person of Mrs Gabe, who mothers us all. Determined to keep our minds off the services during our stay—sound therapy!—she provides civvy clothes for us to wear. No one rousts us out of bed in a morning, we eat at tables set for four, with tablecloths and serviettes, and have the use of an extensive library, games room, radio and wind-up gramophone for entertainment. Despite these relaxations, some odd characters persist on parading round the hostel in full uniform. From the first day of my stay I settle myself at a table with three other victims of the strict regimen of the BMH, all determined to regain lost weight. The bearers soon learn to ask "Second help?" before removing empty plates, and we are dubbed the "wuffing table". I stagger out after lunch into boiling hot sunshine, hugging what shade I can on the mile walk into town. Down to basic shirt, shorts and sandals I pass many staid locals sweating it out in European suits, complete with neckties, and wonder how they survive. Dodging the livestock that wanders unhindered and nibbling at any surviving greenery, I resist the blandishments of rickshaw wallahs, and take refuge from the sun in the bookshops open along the street. I linger a while browsing over stacks of new Penguins on the shelves, to emerge with Nat Gubbins' Over the Fence, Isherwood's Mr Norris, a volume of New Yorker Profiles, and a great prize, an American hardback of Dorothy Parker poems. I return to the hostel with my treasures, rest creaking joints on the lawn, have tea, and natter with other inmates until dusk and foraging skeeters drive us in for a hearty dinner. I play a few records while catching up with a long letter to Marion in the evening, seated at a desk ablaze with a spray of scarlet blooms on one side and a pile of jigsaw puzzles of episodes in the life of the Buddha on the other. I drop off to sleep that night feeling that life has resurned again after a period of suspended animation in the hospital. It is a couple of days later before I find the energy to venture as far as Adgodi camp. Lifts are scarce and I walk most of the way, but it proves worth the effort: when I report to the RAF sick quarters for my medical discharge, the doc glances at my papers and after one look at my wasted frame promptly puts me down for three week's sick leave. When I go to collect a few items from my kit I am further cheered by the sight of an accumulation of mail. I pester the WVS office for gen on places where I can spend this leave. Mysore is conveniently near but, alas, currently out-of-bounds because of outbreaks of plague. An enthusiastic recommendation from behind the counter favours the Nilgiris—the Blue Mountains—as an alternative: I am torn between the attractions of a hostel at Kotagiri ("scenic beauties, hidden among tea plantations, walks, good bus services to other hill stations") and one at Wellington ("convenient for Ootacamund, Coonoor, a playground of the British Raj"). For the outlay of a few rupees a day, either place sounds great, and my trip to Adgodi revealed that back-pay now amounts to some 500 rupees. I complete a lengthy application form for processing by the admin people, which requires final approval of the commanding officer before arrangements can be got under way. I guess I can wait; at least the wheels are set in motion. Months before, with the thought of time hanging heavy in the post-conflict era, I'd enrolled on a London-based correspondence course for the forces on the topic of 'modern art'. Owing to my travels and mail delays, progress to date has been erratic, but in the restful atmosphere of St John's I diligently catch up with things. I find there's a well-stocked library in nearby Cubbon Park, well-stocked with books on Western art and after routine form filling and payment of an entrance fee, subscription and deposit am admitted as a member. With this resource at my disposal my assignments seem less daunting, and I am soon glibly explaining why Millet is a greater realist than Giotto, comparing the painting of Monet and Matisse, writing an essay on the logic of cubism, and having to admit that I have much to learn on the subject. I am often scribbling notes long after everyone else has retired to bed, and find myself talking to Mrs Gabe about my preoccupations. It seems she knew Matthew Smith—has a painting of his, presently tucked away protected from damp during the monsoon period. I latch on to a local weekly journal, Mysindia, with lively political and literary articles and comment. One issue carries an article on Amrita Sher-Gil, an Indian artist who died a few years ago; the black-and-white reproductions of her paintings indicate a forceful talent. Most of the contemporary Indian art I'd seen in Bombay was academic, westernised and boring, but sight of Sher-Gil's work stirs my interest. I wander into the local publishing office to contact the author of the article, Jag Mohan. He is a journalist working in Madras, and my enthusiastic letter of enquiry prompts a three-page reply that is the start of a correspondence discussing Amrita Sher-Gil and contemporary Indian artists in general.

My stay at the hostel ends too soon and I return reluctantly to RAF reality at Adgodi camp. I find the place in turmoil: the radar school staff are in the process of moving their gear down to Ceylon, to make room for an Educational & Vocational Training centre catering for those shortly due for demob. After years in the forces we apparently need brainwashing before we can be safely returned to Civvy Street. Or it could just be another desperate distraction to keep us occupied in the vacuum created by the end of the war. I maintain a low profile, find myself an undemanding job in the drawing office, undemanding in that nobody wants any drawings doing anyway. Happily my leave pass materialises and provides temporary escape from the confusion. I dash into Bangalore for last-minute shopping, acquire a few tubes of watercolour and a grotty sketch pad of local manufacture, in the hopes of doing some painting, and send off two bulging food parcels to relieve the ration situation at home: tea, butter, dried fruit, and a large tin of marmalade. This last item has been hanging around in my kitbag for some time. The routine camp breakfast held few attractions—stodgy porridge followed by baked beans on toast are not a very appetising start to facing the heat of the day—so when we spotted these tins on sale, Jack, Doug and I promptly voted toast and marmalade would be a pleasant change in our diet. We each invested in a tin, opened the first one and shared it, to dispose of the contents before they had chance to deteriorate. We were into the second tin when I was whipped into hospital, and Jack and Doug posted to other stations; so now I am left with the third unopened tin, too big for me to tackle solus... I shake the dust of Adgodi off my chappals and depart in high glee to the city station to catch the train to Wellington. It leaves at dusk. I am alone in a secondclass compartment with upholstered seats but poor lighting. Unable to read I settle under a blanket and doze fitfully until the sun crawls back over the horizon. By then the train is well out on the plains, among palms and paddy fields; vague black masses ahead gradually resolve into mountains, their tops smothered in cloud. On arrival at Mettupalayam, the terminus of the broad-gauge main line, I supervise the transfer of my bundles to the small-gauge 'Blue Mountain Express', a six-coach train pushed by a sturdy little engine, to complete the trip up the towering rain-forest covered slopes of the Nilgiris, to Wellington. To describe this journey as spectacular would be an understatement. We crawl up steep gradients aided by a ratchet track, hugging the mountainside, pass through fairy caves and grottos, ride over magnificent waterfalls on flimsy bridges, catch occasional glimpses of a crazily-angled horizon through damp, drifting clouds. Below us, Mettapalyam becomes an insignificant patch on the landscape, shrinking as we climb. Dazed by the heady grandeur, I dismount at Wellington station to find there's no transport to the hostel. But there are plenty of porters looking for custom; a couple grab my kitbag, bedroll and well-filled tin trunk, hoist them on their heads and jog their way to my destination. I follow them empty-handed; I hate playing this 'burra sahib' role, striding along while older, smaller men carry my burdens, but I've been in India long enough to realise that if you try to buck the system you rob someone of their livelihood. The holiday home, 'Windermere', proves to be an imposing residence, run by a Salvation Army 'colonel' and his family, and hordes of servants. It has a commanding view of Wellington and the mountains on either side. Bags of scope for painting, I glee. The company here is congenial and I soon settle in. Accommodation proves to be excellent: a comfortable bed (and no need to bother with mossie nets), plumbing and sanitation superior to anything I've encountered in the Raj so far, and meeting rooms with large open grates for crackling wood fires on cool evenings. Mornings start with breakfast in bed, and the general fare provided is varied, well-cooked and plentiful. Mind you, there is a small price to pay: being hosted by the Sally Army means that you join in a brief session of hymn-singing after dinner, led by the colonel, in good voice but tone deaf. We rise to the spirit of the occasion, throw out the lifeline with great gusto and promise to be there when they call the roll up yonder. Occasionally harmonium, the colonel, and assembly stray out of phase, with exquisitely dire results. Next day I discard my uniform and don my civvies, my shirt-of-many-colours. An army sergeant across the table from me lifts his arms to shield his eyes from the sight: we'd exchanged wry glances during the hymn singing of the previous evening, nearly busting from suppressed mirth, and in next to no time flat we exchange our life stories to date. Derek hails from Macclesfield and is currently stationed at the hospital at nearby Coimbatore. We join in exploring the locality in between my sketching expeditions. I find painting in watercolours has its problems: the sun rises high, bright and hot in a clear purple-blue sky at these altitudes, my brush dries out almost before it touches the paper, the limited range of paints I have never approaches the subleties of the lush green vegetation—verdant grasslands, tea plantations, shady groves of blue-green wattle and silvery eucalyptus—and the earth is bright red, or is it just the contrast with the prevalent greens that makes it so? My eyes, used to the muted tones of a northern clime, find it hard to come to grips with such raw tropical hues. Ootacamund, generally referred to as Ooty, a nostalgic survival from the heyday of the British Raj, buildings all neat terracotta and white stone trim, neatly set among rolling grasslands, has to be seen to be believed. We gawp at The Club, where the rules of snooker were invented; listen to high falutin' tales of the Ooty Hunt (chasing jackals in lieu of foxes); post letters home in tall scarlet painted cast-iron pillarboxes embellished with the Royal Arms and the VR cypher; retire to a nearby canteen to enjoy toasted crumpets. The whole area proves to be pleasant country in which to walk, explore and, on occasion, get lost. I do it all in changing company: Derek disappears back on duty too soon, but I enjoy meeting other exiles and a surprising number of local folk willing to linger and chat. I never realised I could be so gregarious.

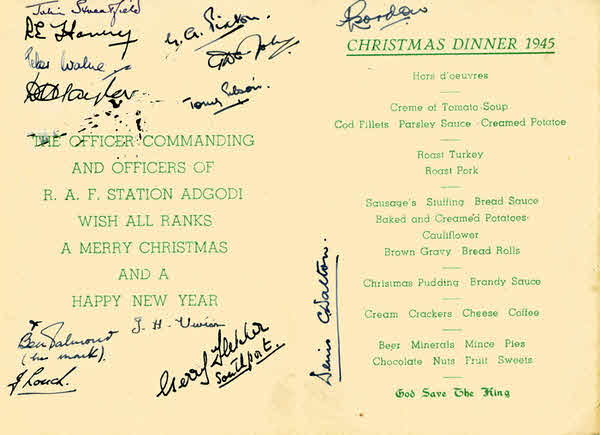

I'd not made a reservation for the return trip; there didn't seem any need. When I descend, late in the afternoon, on the scenic railway—a trip just as breathtaking as the ascent—Mettupalayam seems largely deserted, which is unusual for an Indian station. I find an empty compartment on the train with a sticker on the door claiming it to be reserved for two officers, and settle in there. There's room for eight, so I figure they can't object. This view is shared by a couple travelling to Coimbatore, the next station, who also pile in with their luggage. Inevitably, a transport sergeant then appears, checking reservations, and brusquely tells us to clear out. Since he doesn't return, and there's no sign of the two officers, we stay put. Shortly before the train is due to depart an orderly dashes up and changes the sticker on the door. Curious, I have a quick look: "LAC Turner & Four Mental Cases" it reads. Coincidence or joke? Uneasily, we decide to await developments... there are none, and the train sets off on time. After the couple leave the train, I settle down and doze off, only to be roused during the night by a weird chanting in the adjoining compartment, accompanied by a banging and scraping on the dividing partition. Things quieten down for a while, only to start up more violently. Sounds as though the lunatics have boarded the train after all: I felt a momentary sympathy with LAC Turner trying to cope with them. When I wake next morning, well before the train is due to steam into Bangalore City station all is peaceful, and I just hope my noisy neighbours have already alighted at a station en route. There's no difficulty in scrounging a lift back to Adgodi, where I settle in a conveniently empty hut, roust out the admin types in the orderly room to check on demob news, rescue a pile of redirected mail, and realise, suddenly, that in a fortnight it will be Christmas. My peace is shattered by the arrival of a rowdy contingent from Ceylon, destined for the first EVT instructors course, who take over the rest of the beds in the hut. Seems that apart from the scenery, Ceylon is not a good place to be: things cost four times Indian prices, and all they could send home during their stay was tea, since everything else has to be imported. I find myself elected as a guide on forays seeking bargains in the Bangalore bazaars. It passes the time to the unseasonal Christmas celebrations, when bearers, sweepers, car- and fruit-wallahs, indeed all the casual workers on the station bestow floral garlands on us and hopefully stand back for "Krismuss bakshish". A very traditional Christmas dinner is laid on by the RAF with a free issue of local bottled beer—a very tepid brew. In the hot sunshine I find it hard to work up any enthusiasm, and retire vainly trying to remember what snow was like... and wondering how the folks are coping back home, and if my parcels arrived in time.... ■

© Harry Turner, 1999. |

|