| Malevich Romanov Mystery | HISTORY Page | Obituary Page | |

| |||

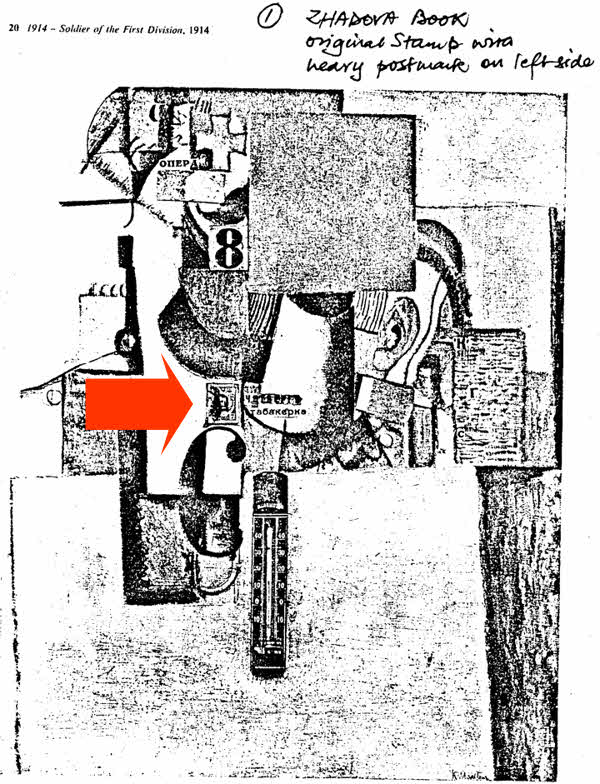

You know how it is when you suddenly notice an odd detail that has previously escaped you... It nags. It's there, blatantly on view, mocking you. So obvious that you marvel how you could possibly have overlooked it. Take the case of the Malevich Romanov stamp... A chance discovery that has become an obsession with me this past few years. I've tried to raise the matter with the owners of the painting concerned, written to an art historian who refers to the work in one of his books, buttonholed people I know in the philatelic field, but all to no avail. All my efforts to resolve the mystery have met with an apathetic silence. Obviously art historians are not interested in boring philatelic details, while philatelists are unconcerned about the niceties of art history. It began for me in 1989, the year there was a major showing of the work of the Russian painter Kasimir Severinovich Malevich in Amsterdam. The works held by the Stedelijk Museum there were supplemented by a generous loan of Malevich's paintings and drawings from Soviet sources—the Leningrad Russian Museum and Moscow Tretiakov galleries—and, lacking only a few masterpieces hoarded in American art museums, it was virtually a retrospective exhibition. Malevich was the painter who dominated the Russian avant-garde movement in the last years of Tsar Nicholas II, and during the revolution and civil war that followed. In that time he moved, logically and resolutely, through cubism and futurism toward total abstraction, reducing painting to pure form with his now-famous Black Square. Malevich continued to play an active part in the Soviet cultural front line of the twenties but fell into disfavour during the Stalinist years, when "formalist tendencies" were denounced and Socialist Realism was all. It was not until the late seventies that a change of stance by the authorities permitted a revival of interest in Malevich's art within the Soviet Union, and an unlocking of archival vaults. So the Amsterdam exhibition created an international stir. Unable to visit it, I obtained a copy of the lavishly illustrated catalogue, and relied on enthusiastic reports from a Dutch friend. He happens to edit the Journal of Russian Philately, for which I do production work. During an exchange of letters, he complained of the absence of his favourite Malevich canvas—The Knife Grinder of 1912. This comment prompted me to check on other American-owned works missing from the show. One of these, of particular interest to philatelists, is a painting-collage of 1914, titled Soldier of the First Division, from a series of cubist-inspired works that Malevich produced before venturing into total abstraction. The work currently hangs in the New York Museum of Modern Art and extends the ideas of Picasso and Braque's cubism of the period. Painted and actual objects are combined in a poetic proto-surrealist manner to evoke deeper meanings, with the images broken by large quadrilateral areas of flat pure colour that presage the sublimities of Malevich's suprematism. There are dissociated representational details—a moustache, an ear, a medal, a bottle—mixed with newspaper cuttings bearing words in Cyrillic ('OPERA', 'THURSDAY', 'TOBACCO POUCH', and the name 'A. VASNETSOV', an artist of an earlier generation) and two objects stuck to the canvas: a thermometer and, bang in the middle of the canvas, a used 7 kopeck stamp, one of the special issues of 1913 commemorating the tercentenary of the ruling Romanov dynasty, bearing a portrait of Nicholas II, destined to be the last of the Tsars. Over the years I've become familiar with several reproductions of Soldier of the First Division, but under the influence of my correspondence, I found myself viewing the illustrations a little more closely than heretofore. There is an excellent full-page monochrome print included in the study of Malevich by the Soviet art historian Larissa Zhadova, published in translation in East Germany in the late seventies, which shows the stamp to bear a heavy circular postal cancellation on the lefthand side. I mentally reviewed my library, convinced that I'd seen a full-colour reproduction somewhere.

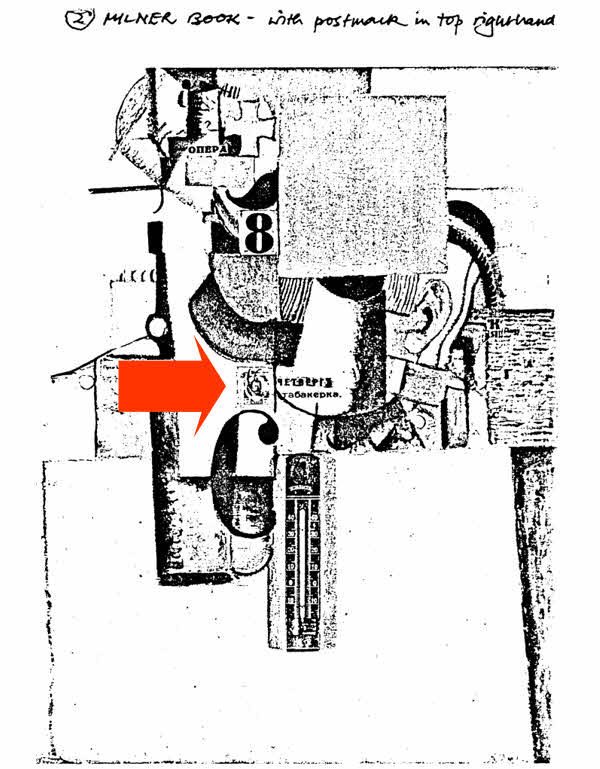

Indeed I had: in John Milner's Russian Revolutionary Art, published in 1979. On comparing these two illustrations I spotted something completely unexpected. The colour version showed a stamp with a different postmark, a lighter cancellation centred toward the top righthand corner of the stamp.

Odd, I mused, and turned to other reproductions. An old Tate Gallery catalogue included a small black and white illustration clearly showing the heavy lefthand postmark on the stamp. The lavish volume produced in the early '80s to accompany the world tour of the Costakis private collection of Russian avant-garde art had a reference to Malevich's painting being acquired by one V.D. Bobrov in the 1920s, and included a photograph of the work passed on to Costakis by Bobrov's widow. This early photograph again shows the stamp with the heavy lefthand postmark. Which suggests that these reproductions show the actual stamp that Malevich pasted on to his canvas way back in 1914. So why does the colour transparency made in recent years from the work now hanging in New York show a completely different stamp? My philatelic curiosity roused, I searched the literature for any reference to this discrepancy. So far as art historians are concerned, when you've seen one used Romanov stamp, you've seem 'em all, since no one had pounced on the change-over. I wrote to the curator of the New York Museum of Modern Art, enclosing photocopies of the two versions of the painting, asking if the replacement stamp was on the painting when it came into his possession, or if the substitution had been made at MOMA and, if the latter, was it intended as "renovation" or "restoration"? I received no reply or acknowledgement of my letter. I recall that an earlier query some years before was also ignored. I presumed that the curator had been on a long vacation and my letter was buried in a pile of correspondence awaiting his attention. But now, I am wondering if it is museum policy not to respond to people asking awkward questions. This silence prompted me to write to Dr. Milner at Newcastle University with the same information, drawing his attention to the fact that the illustration of Malevich's work in his book differed from the rest. He too did not deign to reply. From the art historian's view the apparent loss of the original stamp must surely reduce claims to authenticity. If the actual stamp that Malevich peeled off his correspondence and stuck on his canvas as an Imperial reference was damaged or removed, then 7 kopek Romanovs are in plentiful supply among philatelists, and any dealer worth his salt would provide a replacement with a postmark approximating the well-documented original. So why just slap on the first 7k stamp that came to hand? And if the substitution was made before MOMA acquired the work, why wasn't this discrepancy noticed by the experts at the time? Just asking these questions makes me wonder if my letter set alarm bells ringing at MOMA. Maybe the curator is still panicking about the substituted stamp. Or even about the authenticity of the rest of the collection! Looking at the matter from the point of view of Russian postal history, I guess that Malevich's use of the stamp makes it a unique specimen of the 7k Romanov, and thus a highly desirable item to an insatiable collector. I have a sneaking suspicion that somewhere in its travels, between Russia and America, the painting may have been waylaid by a zealous dealer and its stamp removed to become a prized treasure in an enthusiast's album. Obviously he's not going to shout about it. So there the matter rests. I can only spread the word and hope that some day a young and aspiring art historian looks into the Russian avant-garde and is prompted to repeat my questions, and perhaps force some official answers. Meanwhile, I patiently study the stamp auction lists disposing of Russian collections that come my way, looking for an offer of a unique Malevich Romanov 7k, with that tell-tale heavy postmark on the lefthand side. ■ Harry Turner ©1990 1 August 1989 The Curator The Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street New York USA Dear Sir, While writing some notes on the stamps issued for the Romanov Tercentenary, I had occasion to refer to Malevich's Soldier of the First Division in which a 7 kopek stamp is used as a collage element. The painting Is reproduced, in monochrome, in Zhadova's Malevich (Thames & Hudson, 1982) and in colour in Milner's Russian Revolutionary Art (Oresko, 1979). However, as you can see from the photocopies I attach, on making a comparison I was surprised to find that the stamps shown have different postmarks. That in the Zhadova illustration has a heavy circular cancellation on the lefthand side; the stamp in the Milner version has a lighter cancellation over the top righthand corner. In Russian Avant-Garde Arts: the George Costakis Collection T&H, 1981) there is a reference to the painting being acquired by V.D. Bobrov in the 1920s and, on page 57, there is a reproduction of a photograph of the work given to Costakis by Bobrov's widow. This shows the identical stamp to the Zhadova illustration, which suggests that this was the original stamp used by Malevich. Another stamp must have replaced this by the time the colour transparency used by Milner was made. Can you tell me if the replacement stamp was in place when the painting came into your possession, or has the substitution been made at MOMA? If you made the change, what was the reason—"restoration", renovation? As I have a double interest in this anomaly, both as philatelist and amateur art historian, I should be grateful for any light you can cast on this discrepancy! Sincerely, 26 August 1989 Dr John Milner Department of Fine Art The University Newcastle-on-Tyne NE1 7RU Dear Dr. Milner, In your book Russian Revolutionary Art (1979) there is a colour illustration of Malevich's "Private of the First Division", a painting in which he includes a Romanov stamp and a thermometer as collage elements. The same work is illustrated in Zhadova's Malevich (1978, translated 1982), in monochrome. Comparing the illustrations recently, I was surprised to note that the postmarks on the stamp in each illustration were different, although picture credits were given to the Museum of Modern Art in both cases. Curious at this discrepancy I looked for other illustrations of the painting. In Russian Avant-garde Art: the George Costakis Collection (1981) there is a reference to the work being acquired by V.D. Bobrov, in the 1920s and, on page 57, a reproduction of a photograph of the work given to Costakis by Bobrov's widow. The stamp here has a heavy circular cancellation mark on the left hand side, similar to that in the Zhadova illustration. The stamp in the colour illustration of your book shows a light circular cancellation centred on the righthand corner. (see photostats enclosed). I have written to MOMA enquiring about this point, asking if they can cast any light on the change, but no reply has been received to date. In view of your specialist interest in this area, I wondered if you could help. Sincerely |

|